Artist: BHAGWATI PRASAD /INDIA

Begumpura – A Place Without Sorrow, 2022. Installation with drawings, variable

dimensions.

Photo Credit: Mehmet Çimen

The regal realm with the sorrowless name:

they call it Begumpura, a place with no pain,

No taxes or cares, nor own property there,

no wrongdoing, worry, terror or torture.

Oh my brother, I’ve come to take it as my own,

my distant home, where everything is right.

That imperial kingdom is rich and secure,

where none are third or second—all are one;

Its food and drink are famous, and those who live there

dwell in satisfaction and in wealth.

They do this or that, they walk where they wish,

they stroll through fabled palaces unchallenged.

Oh, says Ravidas, a tanner now set free,

Those who walk beside me are my friends.

– Ravidas

The 15th century leather-working saint, Ravidas strikes a powerful hegemony-defying image in India. The reformist mystic is credited with the vibrant vision of a polity founded on egality, called Begumpura (literally the city without sorrow). Conceived as a utopia without hierarchies, taxes, and surveillance, Begumpura would allow free mobility and full freedom to nurture one’s desires. Reclaiming the socially ordained medium of the saint, i.e. animal hide, Prasad started listening out for the resonances of Begumpura in the contemporary. As the goatskin dries and becomes taut, it is able to take on new vibrations that can ripple through oceans, forests, animals, cities, tools, humans, machines, and plants. Begumpura reveals nature to be a lively medley of myriad agents — chemical, biological, and technical.

Artist: GÜLSÜN KARAMUSTAFA

Dort Panter, Iki seccade, Bir Isa, Bebek Kemanci, Yildizlar ve Tuller (Four Panthers, Two

Praying Carpets, One Jesus, Baby Violonist, Stars and Tulles), 1980 – 2022. Textile collage,

240 cm x 260 cm.

Melankolik Sahmaran (Melancholic Basilisk) , 1980-2022. Textile collage, 120 cm x 160 cm.

Photo Credit: Mehmet Çimen

The two new textile collages by Gülsün Karamustafa invoke the syncretic mix of cultures that define the matrix of Mardin. The works have been composed from fabrics gathered in the 80s by the artist during her travels to the south-east of Turkey as well as those picked up in Istanbul around the same time. This period in time was characterised by a large wave of migration from the eastern and south-eastern countryside to the big cities when the markets were flooded with brilliantly coloured goods, heralding a hybrid new visual sensibility born out of the clash between the metropolitan and immigrant cultures. The current works re-member and rejoice in this border-crossing of material cultures at a time of strained hospitalities and sweeping conservatism.

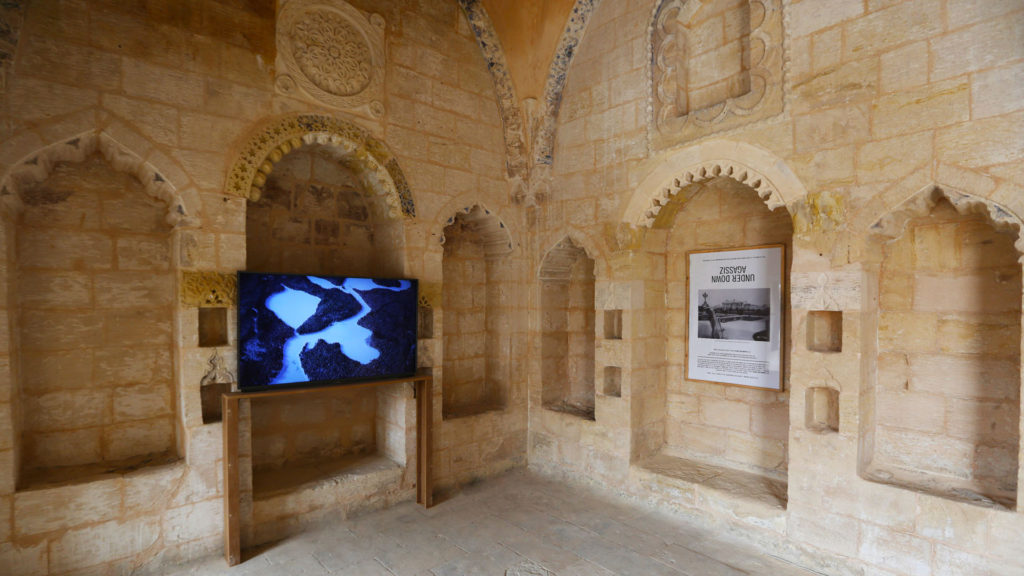

Artist: SASHA HUBER

Sasha Huber (Haiti / Switzerland / Finland)

Karakia – The Resetting Ceremony, 2015. Video, 5 minutes 20 seconds.

Mother Throat, 2017–19. Video, 10 minutes 30 seconds.

Supported by the Arts Promotion Centre Finland.

Photo Credit: Mehmet Çimen

In 2015, Sasha Huber travelled to the Agassiz Glacier on the South Island of Aotearoa, the ancestral Maori name for New Zealand. The artist organised a resetting ceremony there, with a karakia (incantation) offered by Jeff Mahuika, a Maori greenstone carver. This incantation served to symbolically unname the glacier and free it from its association with the glaciologist Louis Agassiz and the racist views he advanced. Subsequently, the artist travelled to Algonquin First Nation and endeavoured to symbolically unname Lac Agassiz (Lake Agassiz) located about 350 km northwest from Montreal, Quebec. She did so in collaboration with Silla, an Inuit throat-singing duo based in Ottawa, featuring Charlotte Qamaniq and Cynthia Pitsiulak. Based on the Inuktitut word Sila, meaning air, climate, or breath, their name speaks to all that connects us to the natural environment. Performing a selection of traditional and contemporary throat songs, they collectively sought to reclaim the site from its legacies of colonialism and racism.

The works are a part of her ongoing De-mounting Louis Agassiz Campaign, started in conjunction with the activist and historian, Hans Fässler. In 2008, Huber made an intervention at the top of an alpine peak in Switzerland, the Agassizhorn (3946 metres) when she placed a metal plaque bearing a graphic representation of the Congolese-born slave Renty, whom Agassiz had ordered to be photographed on a South Carolina plantation “to prove the inferiority of the black race”. In so doing, the artist took the first step towards renaming the mountain. Subsequently, a formal request was submitted to the councils concerned for the plaque to be permanently fixed to the rocks on the summit, and for the mountain to be renamed. An international petition (www.rentyhorn.ch) addressed to the Swiss government and its two chambers of parliament remains online for signing.

Artist: SERVER DEMIRTAS

Çiglik 2 (Scream 2), 2020. Animatronic sculpture, 111 cm x 44 cm x 67 cm. Supported by

Bozlu Art Project Collection.

Photo Credit: Mehmet Çimen

Server Demirtas’s animatronic sculpture portrays a screaming woman, wrinkled with age. The work recalls the science-fiction author, Ursula Le Guin’s upholding of the crone as an exemplar of the human race. Having liberated herself from reproductive / social obligations, and armed with unique experiences and wisdom, the crone signified to Le Guin an ideal spokesperson for humanity. The visceral scream also evokes the Korean American artist Johanna Hedva’s articulations of pain as well as the disassociation it causes from the body, in their ‘sick woman theory’. Hedva finds mystical and socialist potentials in pain through her analysis of experiences of female mystics. Occupying a sacred cove composed of some of the oldest rocks in Mardin, the screaming woman gestures towards all of these potentials.

Uriel Orlow (Switzerland)

Dedication, 2021. Single-channel video installation, 1 minute 20 seconds.

Photo Credit: Mehmet Çimen

Dedication is a paean to the symbiotic relationship between root systems of plants and fungi, evidently an underacknowledged basis of life for us too. They form social, cooperatively functioning systems that communicate with each other underground across kingdoms. Like superorganisms, they exchange nutrients and water, or warn each other of pests, communicating vitality and vulnerability in a communal exchange. This traditional knowledge of networks and interdependencies governing natural systems, now scientifically proven, was forgotten with humanism, the Enlightenment and subsequent industrialisation, when humans began to exploit nature as the “crown of creation.” Communal exchange and mutual care inherent in the symbiotic mechanisms of the plant kingdom, could also illuminate alternative models for human societies. Our systems designed for egoism and isolation are metaphorically contrasted with naturally existing mutualist modalities. As a part of nature, humanity gains a potential for resistance, adaptation and regeneration.